Product docs and API reference are now on Akamai TechDocs.

Search product docs.

Search for “” in product docs.

Search API reference.

Search for “” in API reference.

Search Results

results matching

results

No Results

Filters

Introduction to DNS on Linux

Traducciones al EspañolEstamos traduciendo nuestros guías y tutoriales al Español. Es posible que usted esté viendo una traducción generada automáticamente. Estamos trabajando con traductores profesionales para verificar las traducciones de nuestro sitio web. Este proyecto es un trabajo en curso.

The Domain Name System (DNS) is a worldwide directory that maps names to addresses and vice versa. It also provides many other types of information about computing resources. Although the DNS operates largely hidden from view, the global Internet would not work without it.

This guide explains what DNS is, how it works, and how to build your own authoritative name server.

This is the first in a series of four DNS guides. Future guides cover primary and secondary name server setup, securing DNS with DNSSEC, and other security measures to address user privacy concerns.

What Is DNS?

DNS is a global directory of computing resources. It can locate servers, PCs, phones, IoT devices, routers, switches, and essentially anything with an IP address. DNS also holds information linking computers to security keys, services such as instant messaging, GPS coordinates, and much more.

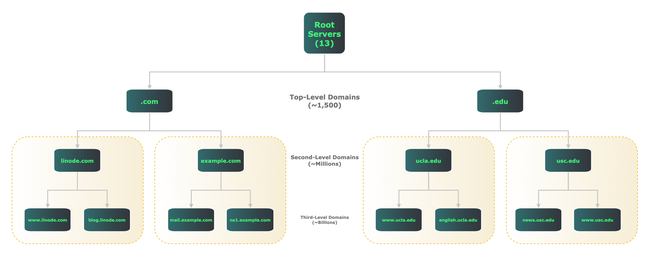

DNS design is hierarchical and distributed. The diagram below illustrates both points. It shows how DNS divides all resources into domains, and delegates different levels of name servers to provide information within each domain.

At the top of the DNS tree are the root servers, usually referred to by a single dot ("."). The root servers are actually comprised of 13 different sets of servers, each operated by a different organization. They act as a starting point for all other parts of the hierarchy.

Below the root servers are top-level domains (TLDs). Common TLDs include .com, .edu, and .org, but there are currently around 1,500 TLDs.

Further down in the hierarchy are second- and third-level domains, and so on, referring to their distance from the root. The domain example.com is an example of a second-level domain, while engineering.example.com is a third-level domain.

Regardless of level, all DNS name servers provide information about items within their domains. For example, linode.com name servers provide information about hostnames, addresses, mail servers, and name servers within that domain.

How Does DNS Work?

DNS clients use recursion, the concept of repeating a process multiple times using information gleaned from the previous step, to learn how to locate resources.

For example, when visiting www.linode.com, your system first conducts a series of recursive DNS exchanges to learn the server’s IP address before it can connect with the Linode web server.

First, your client checks to see if it has an IP address for the Linode webserver in its local cache. If not, it asks your local DNS server.

If the local DNS server doesn’t have an IP address in its cache, it then asks one of the root servers how to reach www.linode.com. The root server replies, essentially saying “I don’t know, but I see you’re asking about something in the .com domain. Here are some IP addresses for .com name servers”.

Your local DNS server then repeats its query, this time to a .com name server. The .com name server replies, “I don’t know, but I can tell you the IP addresses of name servers for linode.com”.

The local DNS server then asks, for the third time, what IP addresses correspond to the hostname www.linode.com. This time, the linode.com name servers are authorized to provide a direct answer to your question.

A Linode name server responds with IP addresses for the Linode web server. Your local DNS server passes along that information to your client, and caches it for future use.

Finally, your system has an IP address for the Linode web server. It can now set up a TCP connection and make an HTTP request.

Before you could retrieve the web page, your client and the local DNS server had multiple conversations with three outside sets of DNS servers, plus your local DNS server, just to get an IP address.

Believe it or not, that’s a relatively simple example. A popular commercial site, such as a news site, has advertising and other embedded third-party content. This could require having these sets of DNS conversations several dozen times, or more, just to load a single page.

While all this occurs in milliseconds, it underscores how critical DNS is to a functional Internet. Everything begins with a series of DNS queries.

Types of DNS Servers

There are several types of DNS servers: authoritative (both primary and secondary), forwarding, and recursive. All three types may reside on a single server, or may be assigned to separate dedicated servers for each type. Regardless of location, these servers work cooperatively to serve DNS information.

An authoritative server provides definitive responses for a given zone, which is a set of computing resources under common administrative control. While non-authoritative DNS servers may also store and forward answers about a zone’s contents, only an authoritative server can provide definitive answers.

A zone may be a domain such as linode.com, but there isn’t always a 1:1 relationship between domains and zones. Authoritative servers may delegate authority to subdomains. For example, the .com authoritative servers delegate responsibility for linode.com to Linode’s name servers. In this case, linode.com is part of the .com domain, but .com and linode.com represent different zones.

Each zone should have at least two authoritative name servers, for both redundancy and load-balancing of user queries. This guide covers setup of a primary name server.

Both primary and secondary name servers are authoritative, and appear nearly identical to the outside world. However, secondary name servers automatically receive all zone updates from the primary name server. After initial setup, zone configuration changes only need to be made once, on the primary name server. It then automatically pushes out all updates to any secondary name servers.

A forwarding server is one that makes external DNS requests on behalf of clients or other DNS servers. Your local DNS server, while not authoritative for most zones, is most likely either a forwarding server itself, or configured to send requests to one. When you ask for a DNS resource outside your zone, a forwarding server finds that resource.

A recursive resolver makes DNS queries, either for itself or on behalf of other clients, and optionally caches the replies. As with any type of caching, it’s best to store information as close as possible to your client. While your local client may perform recursion, your local DNS server almost certainly does.

By far the most common DNS server software is Bind 9, the open source package maintained by the Internet Systems Consortium. Bind can function as any type of DNS server. It also supports many DNS extensions that go well beyond it’s original design goals.

Because of Bind’s age and size, some users prefer smaller, more modern DNS implementations. Two of the more popular are NSD, an authoritative-only name server, and Unbound, a resolver that also does forwarding and caching. This guide covers authoritative name server setup using NSD.

Resource Records

Before diving into setup details, familiarize yourself with the different types of information DNS can provide within a given zone. Think of DNS as a distributed database, and zones as tables within the database. Resource records (RR) are entries within each table.

Each record describes a different type of information. For example, “A” records associate one hostname with one IPv4 address, while “AAAA” records do the same for IPv6.

There are dozens of RR types; this Linode guide covers some of the most common and important ones. Most authoritative name servers need at least the following RR types:

- A: Maps a hostname to an IPv4 address.

- AAAA: Maps a hostname to an IPv6 address (pronounced “quad-A”).

- MX: Identifies a mail server for a given zone, and gives its priority.

- NS: Identifies a name server for a given zone.

- SOA: (Start of Authority) lists primary name server, administrative email contact, serial number, and default timers for a given zone.

The above list is enough for a bare-bones setup, but other common RR types include:

- CNAME: Maps a hostname alias to a hostname defined in an A or AAAA record.

- PTR: Maps an IP address to a hostname (sometimes referred to as “reverse DNS” or “rDNS”).

- TXT: Provides information in text form and often aids in email security through use of SPF, DKIM, and DMARC records.

Before You Begin

If you have not already done so, create a Linode account and Compute Instance. See our Getting Started with Linode and Creating a Compute Instance guides. This guide is for Ubuntu 22.04 LTS instances.

Follow our Setting Up and Securing a Compute Instance guide to update your system. Set the timezone, configure your hostname, and create a limited user account. To follow along with this guide, give your server the hostname

ns1and configure the hosts file as follows:- File: /etc/hosts

1 2 3127.0.0.1 localhost 203.0.113.10 ns1.yourdomainhere.com ns1 2600:3c01::a123:b456:c789:d012 ns1.yourdomainhere.com ns1

Replace the example IP addresses with your Linode instance’s external IPv4 and IPv6 addresses, and

yourdomainhere.comwith your domain name.

sudo. If you’re not familiar with the sudo command, see the

Users and Groups guide.Building an Authoritative Server

After completing the prerequisite steps above, it’s time to build a primary authoritative name server using NSD.

Install NSD

Open an SSH session to your instance and install NSD:

sudo apt install nsdConfigure the NSD control utility,

nsd-config:sudo nsd-control-setupThe output should appear as follows:

setup in directory /etc/nsd removing artifacts Setup success. Certificates created.If not, check

/var/log/syslogfor errors.

The nsd.conf File

As packaged for Ubuntu 22.04 LTS, NSD’s main configuration file (nsd.conf) points to other files in /etc/nsd/nsd.conf.d, but that directory is empty by default.

Since the NSD documentation already includes a fully annotated sample configuration file, copy that file and work from there. The sample file lists many options with plenty of comments, making it a useful learning tool.

First, gather your Linode’s external IPv4 and IPv6 addresses. Follow this guide to Find Your Linode’s IP Address or use the following command:

ip aIdentify all configured IP addresses except those on loopback interfaces or those with local-link (

fe80::) addresses.1: lo: <LOOPBACK,UP,LOWER_UP> mtu 65536 qdisc noqueue state UNKNOWN group default qlen 1000 link/loopback 00:00:00:00:00:00 brd 00:00:00:00:00:00 inet 127.0.0.1/8 scope host lo valid_lft forever preferred_lft forever inet6 ::1/128 scope host valid_lft forever preferred_lft forever 2: eth0: <BROADCAST,MULTICAST,UP,LOWER_UP> mtu 1500 qdisc mq state UP group default qlen 1000 link/ether f2:3c:93:c7:0c:d5 brd ff:ff:ff:ff:ff:ff inet 45.79.218.211/24 brd 45.79.218.255 scope global eth0 valid_lft forever preferred_lft forever inet6 2600:3c02::f03c:93ff:fec7:cd5/64 scope global dynamic mngtmpaddr noprefixroute valid_lft 60sec preferred_lft 20sec inet6 fe80::f03c:93ff:fec7:cd5/64 scope link valid_lft forever preferred_lft foreverIn the example output above, the pertinent IP addresses are

45.79.218.211(IPv4) and2600:3c02::f03c:93ff:fec7:0cd5(IPv6).Change into the

/etc/nsd/directory and preserve the original file by creating a copy with the.origextension:cd /etc/nsd sudo mv nsd.conf nsd.conf.origNow copy the original file to

/usr/share/doc/nsd/examplesand open it:sudo cp /usr/share/doc/nsd/examples/nsd.conf.sample nsd.conf sudo nano /etc/nsd/nsd.confNote that

nsd.confcomments out allip-addressstatements, meaning NSD attempts to listen on all addresses by default.NSD does not start unless you explicitly configure your system’s external IP addresses. That’s because Ubuntu’s

systemd-resolvedprocess already binds to TCP and UDP ports53on thelocalhostaddress.Since the

localhostaddress is already in use, simply binding to all addresses won’t work. Because NSD is an authoritative-only name server serving external clients, it can bind to external addresses without affecting the system’s ability to resolve addresses on thelocalhostaddress.Uncomment two

ip-addressstatements in theserver:section of thensd.conffile, substituting your system’s addresses for these examples:- File: /etc/nsd/nsd.conf

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 27server: # Number of NSD servers to fork. Put the number of CPUs to use here. # server-count: 1 # Set overall CPU affinity for NSD processes on Linux and FreeBSD. # Any server/xfrd CPU affinity value will be masked by this value. # cpu-affinity: 0 1 2 3 # Bind NSD server(s), configured by server-count (1-based), to a # dedicated core. Single core affinity improves L1/L2 cache hits and # reduces pipeline stalls/flushes. # # server-1-cpu-affinity: 0 # server-2-cpu-affinity: 1 # ... # server-<N>-cpu-affinity: 2 # Bind xfrd to a dedicated core. # xfrd-cpu-affinity: 3 # Specify specific interfaces to bind (default are the wildcard # interfaces 0.0.0.0 and ::0). # For servers with multiple IP addresses, list them one by one, # or the source address of replies could be wrong. # Use ip-transparent to be able to list addresses that turn on later. ip-address: 45.79.218.211 ip-address: 2600:3c02::f03c:93ff:fec7:0cd5

Next, move down to the file’s

remote-control:section. Find thecontrol-enableline, uncomment it, and changenotoyes:- File: /etc/nsd/nsd.conf

1 2 3 4remote-control: # Enable remote control with nsd-control(8) here. # set up the keys and certificates with nsd-control-setup. control-enable: yes

This allows you to add, remove, and edit DNS entries using the

nsd-controlutility without having to restart the NSD server every time.When done, press CTRL+X then Y and Enter to save and close the file.

Verify that the configuration is valid with the

nsd-checkconfutility (you don’t needsudofor this):nsd-checkconf /etc/nsd/nsd.confIf there are no errors, restart the NSD daemon:

sudo systemctl restart nsd

Creating a Zone File

A functional authoritative name server is now set up, but it’s not yet serving any zones. This example creates a zone file for the domain yourdomainhere.com, substitute your domain name as appropriate.

Although this guide only creates an authoritative (master) zone, create directories for master and secondary zone files anyway:

sudo mkdir -p /etc/nsd/zones/master sudo mkdir -p /etc/nsd/zones/secondaryNow create a zone file. This zone handles all forward queries (those seeking to translate hostnames to IP addresses).

sudo nano /etc/nsd/zones/master/yourdomainhere.com.zoneAdd these contents to the file, substituting your domain name and IP addresses as appropriate:

- File: /etc/nsd/zones/master/yourdomainhere.com.zone

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 28 29 30 31$ORIGIN yourdomainhere.com. $TTL 3600 ;; SOA Record @ IN SOA ns1.yourdomainhere.com. hostmaster.yourdomainhere.com. ( 2023030701 ; serial 3600 ; refresh (1 hour) 900 ; retry (15 minutes) 2419200 ; expire (4 weeks) 3600 ; minimum (1 hour) ) ;; A Records ns1 A 96.126.102.178 ns2 A 96.126.102.178 john A 96.126.102.179 paul A 96.126.102.180 george A 96.126.102.181 ringo A 96.126.102.182 stu A 96.126.102.180 ;; AAAA Records ns1 AAAA 2600:3c01:0:0:f03c:93ff:fe01:4070 ns2 AAAA 2600:3c01:0:0:f03c:93ff:fe01:4070 john AAAA 2600:3c01:0:1:f03c:93ff:fe01:4071 paul AAAA 2600:3c01:0:2:f03c:93ff:fe01:4072 george AAAA 2600:3c01:0:3:f03c:93ff:fe01:4073 ringo AAAA 2600:3c01:0:4:f03c:93ff:fe01:4074 stu AAAA 2600:3c01:0:2:f03c:93ff:fe01:4072 ;; MX Records @ MX 10 stu.yourdomainhere.com. ;; NS Records @ IN NS ns1.yourdomainhere.com. @ IN NS ns2.yourdomainhere.com.

There are a couple of things to note in the zone file:

First is the zone file syntax. Comments always begin with one or more semicolons (";"). Using a hash mark ("#") or any other character for comments results in a syntax error when the

nsd-checkzoneutility is run. It also causes the zone not to load.Second, notice that the records for

paulandstupoint to the same IP addresses, as dons1andns2. This underscores an important aspect of DNS: one hostname can refer to many addresses, and vice-versa. It is this capability that makes virtual hosting possible.While

paulandstuonly share the same IP address for demonstration purposes,ns1andns2sharing an IP address has actual utility. Many domain registrars require a minimum of two name servers to utilize custom DNS. Since this guide only sets up a single primary name server, having records for two name servers allows you to proceed with domain delegation. The second part of our series on DNS covers how to set up a secondary name server on a separate Linode instance.Third, note that fully qualified hostnames always have a period appended, representing the parent zone:

@ MX 10 stu.yourdomainhere.com.Omitting that final period, causes the NSD daemon to append the entire domain name, creating a pointer to a nonexistent resource (e.g.

stu.yourdomainhere.com.yourdomainhere.com). Omitting the final period in zone files is the single most common DNS configuration error.Avoid this issue with the

$ORIGIN yourdomainhere.com.macro that begins this zone file. This tells the NSD daemon to append “yourdomainhere.com.” to any host or domain name not ending with a period. For example, with$ORIGIN yourdomainhere.com.applied, these two A records are functionally identical:john A 96.126.102.179 john.yourdomainhere.com. A 96.126.102.179Again, note the final period when using the full form.

When done, save and close the file.

Use the

nsd-checkzoneutility to verify the zone file’s syntax:nsd-checkzone yourdomainhere.com /etc/nsd/zones/master/yourdomainhere.com.zoneThe NSD server should return:

zone yourdomainhere.com is okIf not, the command outputs the syntax errors causing the error.

Next, configure the NSD server so that it responds to queries for the newly created zone. Open the NSD configuration file again:

sudo nano /etc/nsd/nsd.confTowards the end of the file, uncomment the

zone:section along with thename:andzonefile:entries. Add your domain name and zone file as shown below:- File: /etc/nsd/nsd.conf

1 2 3 4 5 6 7zone: name: "yourdomainhere.com"" # you can give a pattern here, all the settings from that pattern # are then inserted at this point # include-pattern: "master" # You can also specify (additional) options directly for this zone. zonefile: "zones/master/yourdomainhere.com.zone"

For any additional zones you create in the future, simply repeat this step, starting with a

zone:statement. Note that the zone file locations are relative to/etc/nsd, so the full pathname is not necessary.When done, save and close the file.

Validate the configuration file’s syntax:

nsd-checkconf /etc/nsd/nsd.confIf the server returns no errors, restart the NSD service:

sudo systemctl restart nsd

Delegation at Your Registrar

The final step is to delegate name service to the new server at your domain registrar.

Every registrar’s management tool allows you to delegate DNS to one or more name servers for your domain. Usually, the registrar needs the hostname and IP addresses for each name server. Be sure to point to the new name server’s hostname and IP address.

ns2.yourdomainhere.com alongside ns1.yourdomainhere.com, and provide the same IP address for both.In theory, delegation changes can take 24-48 hours to propagate through the global Internet. However, in practice propagation usually happens much faster, often in 5 minutes or less.

Test Your Setup

Test the new setup with queries for DNS resource records. One popular command line tool for this is dig, which is already included with Linode’s Ubuntu 22.04 LTS instances.

Use the -t switch to specify which RR type you want to query. The following example asks for NS records for yourdomainhere.com, replace yourdomainhere.com with your own domain name:

dig -t NS yourdomainhere.comThe server should respond (in the “ANSWER SECTION”) with the hostname of your new name server:

; <<>> DiG 9.18.1-1ubuntu1.3-Ubuntu <<>> -t NS yourdomainhere.com @ns1.yourdomainhere.com

;; global options: +cmd

;; Got answer:

;; ->>HEADER<<- opcode: QUERY, status: NOERROR, id: 18821

;; flags: qr aa rd; QUERY: 1, ANSWER: 1, AUTHORITY: 0, ADDITIONAL: 2

;; OPT PSEUDOSECTION:

; EDNS: version: 0, flags:; udp: 1232

;; QUESTION SECTION:

;yourdomainhere.com. IN NS

;; ANSWER SECTION:

yourdomainhere.com. 3600 IN NS ns1.yourdomainhere.com.

yourdomainhere.com. 3600 IN NS ns2.yourdomainhere.com.

;; Query time: 0 msec

;; SERVER: 2600:3c01::f03c:93ff:fe01:4070#53(ns1.yourdomainhere.com) (UDP)

;; WHEN: Wed Mar 08 05:53:39 UTC 2023

;; MSG SIZE rcvd: 168Verbose output can be extremely useful in troubleshooting. However, if you don’t need all that detail, just add the +short flag to the query. Here’s the same query again with just the response:

dig +short -t NS yourdomainhere.comns1.yourdomainhere.com.

ns2.yourdomainhere.com.Conclusion

You now have a working authoritative name server. Other DNS guides cover redundancy with primary and secondary name servers, securing DNS with DNSSEC, and user privacy issues.

DNS is the essential glue that ties together the global Internet. You can opt to use Linode’s free DNS service for cloud operations, or set up your own name server as described here. Either way, a solid understanding of the protocol puts you in ultimate charge of your domain and all resources within it.

More Information

You may wish to consult the following resources for additional information on this topic. While these are provided in the hope that they will be useful, please note that we cannot vouch for the accuracy or timeliness of externally hosted materials.

This page was originally published on